Difference between revisions of "Arcane University:Writing"

(→General) |

m (→About the Characters Stake in the story) |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

* something they fear | * something they fear | ||

* something they gain | * something they gain | ||

| − | * something they | + | * something they lose |

And, of course, if possible, every actor should have each different from each other! Some should be the noble part, others the mean ones, some altruistic, some merchants,… | And, of course, if possible, every actor should have each different from each other! Some should be the noble part, others the mean ones, some altruistic, some merchants,… | ||

Revision as of 03:59, 28 June 2020

This is the main page of the Beyond Skyrim Arcane University Writing tutorials.

Contents

- 1 General

- 2 General Workflow

- 3 Exposition Writing Tutorials

- 4 Environmental Writing Tutorials

- 5 Tool-specific Guidelines and Links

General

Purpose

A writer needs to have profound knowledge of the mechanisms of the game, the history and lore, and most importantly, the unique feeling and methods of making the player feel richly rewarded by his presence in the game world. Writing is a vast field. It includes the most creative opportunities to shape a new concept of a game. But it is also the most critical step because it can provoke structural difficulties, which are hard to overcome in later stages, especially if those stages are not sufficiently considered before. These include the capabilities of Level Design and Implementation. Those have to be able to realize the scenario and still achieve an interesting and evenly paced game experience. Like all fields of game development, writing must be evaluated by the finished content. Did it help the game? Or did it create issues? But even more than any other field, it is a first big step, setting frames and borders and sketching the world and characters. It can potentially annihilate the opportunities of other departments to work with the given writing if those borders are too tight. On the other side, it can also push other departments into completely new experiences and levels, unleashing their potentials, which is the real intention.

Categories

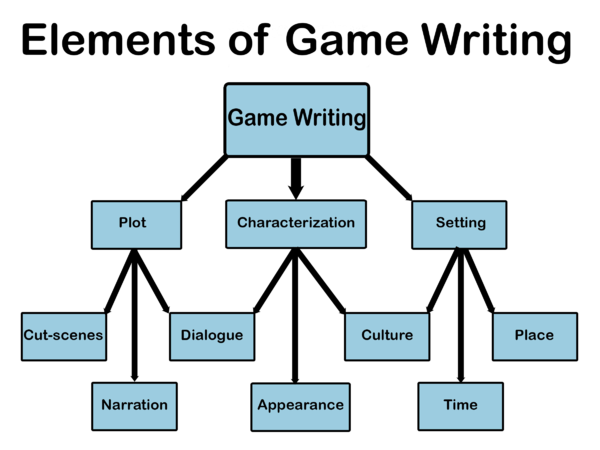

There are different uses for writing when working on games. Also, there are many methods and as many writing styles as there are authors, and all of them are legitimately following their visions. It makes no sense to block ideas, concepts would starve. But before having great ideas, its good to have a decent understanding of how these ideas could be potentially used and how much space is available for them.

World and Plot Drafts, Environmental Writing

There are the lore texts and world primers, which try to sketch out a world entirely. Those can include the most details and fantasy and give you great inspiration. But sadly, those also often lack the condensed and defined shape of exposition and dialogue that will make it later in the game. Also, they lack the direct tie to the player and his/her current situation in the world, his intrinsic motivation (more about that below). It can be seen as a general brainstorming, and the more ideas are discussed and combined and filtered, the better. This might even take several years. But ultimately, when the world is far in the implementation process, this lore should be solid and not altered too much, to avoid inconsistencies and reworks in the following departments (Level Design, Implementation and sometimes even the 3d-Design or Concept art, such re-iterations can be avoided by taking decisions together and building workarounds rather than deleting everything since the team also has a responsibility to accomplish the set schedule).

Exposition and Dialogue

This is where it gets interesting. As we will discuss below, games offer only a tiny amount of space to place your info and dialogue. This information has to be chosen very carefully, packed and placed well and include everything relevant, but nothing else. Unlike environmental writing, it cannot contain all details and there has to be a filtering and selection process between the above stage and the “in-game writing”.

“Why discussing in-game writing deeply when writing is a free, creative and individual process?”

You will find that there are general limitations that have to be mastered inside the game. Each game has its own ways to bring texts, words, and dialogues to life. These have to follow the general pace of the player’s situation. It should also be the right amount of information, and it should be relevant. One can find some general rules working with Dialogue and Exposition. You are free to do it your way, but it might be useful advice on what some experienced game writers said. We gathered some condensed excerpts of their speeches for you.

What is Exposition and its general purpose?

Exposition is the direct dialogue that carries the narrative. It should be split into slices to make them digestible most important info at the end of dialogue just one piece of important information at once (per dialogue) the type of information chronologically gathered should follow logical order characters presenting this information should have valid reasons to give them “The general purpose of dialogue is to move the player forward!” -> Dialogue does not offer the space to tell a background story in general.

Common examples of wrong use of Exposition

- “Let me tell you how our people started in stone age…” -> The writer's history encyclopedia issue. player reaction: fall asleep.

- “The evil empire killed all good people…” -> The oversimplification issue. player reaction: perceiving an artificial, inorganic and generic the story.

- “Dragons used dirty bombs and nuked our battle mechs with Magicka” -> The Publicity-exaggeration issue/ commercial keyword issue. player perception: artificial, un-immersive overcooked story.

- “Once in the days of old, we captured the Mines of Moria, and Whiterun, and….” -> The lead level designer showing off random unrelated locations in the game issue. player perception: what bulk of irrelevant information, tired.

- “Oh, and when you go there, gather 20 Goblin skulls for me!” -> The Quality department realized the emptiness of contents/tasks before shipping, added random things issue. player perception: it's generic, artificial and impersonal and un-immersive.

The primary Purpose of Exposition

- What is happening?

- What do I do?

- Where do I have to go next?

must - extrinsic motivation, plot-critical info: “This Dragon will eat Nirn!”

should - intrinsic character motivation: “This dragon killed your father!”

could - additional lore and realism (optionally, if not breaking game flow!): “How did we find out that he will destroy Nirn? Well, …”

should not - irrelevant/stopping game flow: “Let me tell you about the life cycle of dragons…”

The secondary purpose of Exposition

Adding to environmental writing. Examples:

- Codex (encyclopedia)

- in-game books (journals, books, scrolls…)

- ambient dialogue (if the Thalmor spy would say something to a guard when you visit him; you could overhear it and go on or stay and listen)

- optional questions (How did you meet character a, character b? -> above, category 3, could)

- environmental storytelling (level design and graphical design, music…)

- auxiliary products (card games etc, not for us)

Working with a complex background story

To avoid getting stuck in details, the only way is to analyze the relevant key pieces of information and to serve them in bite-able chunks where it is necessary.

Example: "The ancient crown went missing has elven magic. the elven kingdom was west of where you are. it was destroyed by a war with the goblin king." -> the player only remembers one last thing in each dialogue.

The strategy of breadcrumb trails

What (motivation) or: know about the crown

Why (connection) or: realize there are runes with elven magic

Where (location) or: find a scholar who can translate them

How (method of interaction) or: read the runes yourself

Pitfalls using the Bread Crumb Trail:

- “Maybe the Elves know something!”… Problem: The Player has no idea where the next NPC is and how to proceed with the story. Their perception is not: “Wow. this is challenging, I should keep trying…” but rather: “Your game does not work, it is broken and it sucks.” “go there and do this” -> pack it, so it does not appear as the designers manipulate the player in a certain direction but rather like “you have this choice, and there will be your reward”. (Quest Objectives)

- “Let me tell you a story”… Problem: irrelevant information gets ignored and disturbs the game flow. (check the 4 W’s about Motivation and Hook up above for better use)

- “Red Herrings” Each bit and piece of information is expected to be relevant and important; giving irrelevant information (and having the player remembering it without reward) will make him frustrated. Player perception will not be “Oh, I was stupid to try that and go there.” but rather: “Your Game is broken and it sucks.”

Show, do not tell!

(or: how to pack exposition in the game) “Exposition is the bitter pill to swallow information; Characterisation can be the chocolate coating to make it more appealing.”

Speakers Position, Style, and Perception

Framing the Exposition with a believable character -> the information given must be an integral component of the character's own life story. You should not be able to replace a character by a road sign “bandits this way!” – then, something went horribly wrong!

Ask yourself, what would the characters say, if it was themselves? Consider topics of their environment, daily life, and social group, plus their unique character.

Speakers Messages (Subtext and Analogies)

The subtext is raised out of the world's background, Plot, Characters, and his/her feelings. The example below from a scene we all know: See, why scene 1 is good, and scene 2 feels “off” because of the perception of Han Solo’s Character we all have?

Analogies

Whenever you can package Exposition in an analogy using consistent terms of a world, you can avoid making an “artificial, top-down birds-eye analysis” which would break the immersion of the scene entirely. Also, analogies can be understood subconsciously and quicker and be remembered longer, using metaphors and pictures. Example: Do not say “you need to explain to them their feelings” but rather “tell them, this is normal, this is your anger, and this is your happiness.” It will get one level closer to the reality of the recipient and less meaning is lost in translation between implied message content and the receiver level. You do not exactly say what you mean, but portray it. making it more impressive and lasting.

This applies only for non-immediate and non-interactive info; that info should all go in subtext and / or analogies! (obviously “run for your lives!” does not go there as it requires immediate action! 😉 )

About the Characters Stake in the story

What is the personal connection of the Character? What are his feelings regarding the plot and other characters and the environment? Every speaker should have all of these elements: (The 5 personal ties of a speaker)

- something they want

- something they need

- something they fear

- something they gain

- something they lose

And, of course, if possible, every actor should have each different from each other! Some should be the noble part, others the mean ones, some altruistic, some merchants,…

How much Emotion?

Like in music and painting and theater play, it is best to first give a stronger emotion, and later tune it down, the opposite way will get very hard with writing. “go there.” (how could a voice actor invoke much emotion in this anymore? 😉 )

The Player – NPC relation

Start considering the dialogue from both sides:

- What does the player want to / need to hear (for story progress)?

- What does the NPC want to / would be willing to tell, and what does he/she usually think of?

- “A Janitor is more memorable than a commander, because he has a more personal relationship to his environment, and not all of his character is filled by his assigned role.”

- “Characters who are not as we expect them, like a commander who is not a fierce strategist, or a janitor who is actually a warrior, are memorable and noteworthy and have character; but the general dummy characters based on stereotypes are killing the credibility of your story.”

- The exposition is telling. -> direct dialogue

- The characterization is showing. -> show emotional reactions on events and plot!

Example: You don’t say “he hates the empire” but you find out he was imprisoned and later after a battle that he is in the secret resistance. You can and should split this information over time. And do this for all relevant characters, as space of the game plot allow it. Then you come to the point where the player asks themselves “What else might we know about a character?”. The player will start guessing what kind of person the character is, and most can be left vague, but it will be an interesting actor.

Stereotypes

Nobody wants to see stereotypical actors. The blonde cliche women, the idiot boy, the super hulk, …rather do some research on the roles of your actors and their possible background and social relations, but most importantly, besides their official roles and their self-understanding, imagine them as human beings. Credible humans are, in doubt, more convincing than perfectly sketched actors for their “roles” who lack any character. That means, in doubt, give your characters 60% persona and individual character that might even conflict with the role their environment puts them in; and for the remaining 40% try to get a good idea of what role this character players play in their world. Some personas might support their roles, as having chosen them, others might not.

Summary

- Dialogue should be the solution to a player's problem.

- The characters who deliver the dialogue and the way of speaking should be carefully considered

- Try to “get in the head” of the speakers.

- Do it like for a musical, the time horizon of an RPG is similarly short and fluid

- Remember that you have a tiny amount of time to place information in a fluid and dynamic game environment